Jacques Tati was a film maker from Paris who spent his life creating comic films with elaborate scenery and little dialogue. His most popular films (Mon Oncle and Play time) centered on the dimwitted yet lovable character of Monsieur Hulot and his quixotic struggle with postwar France’s infatuation with modern architecture, mechanical efficiency and American-style consumerism. Mon Oncle and Playtime were largely visual comedies; color and lighting are employed to help tell the story. The dialogue is barely audible, and largely subordinated to the role of a sound effect. Consequently, most of the conversations are not subtitled. Instead, the drifting noises of heated arguments and idle banter complement other sounds and the physical movements of the characters, intensifying comedic effect. The complex soundtracks also use music to characterize environments, including a lively musical themes that represent Hulot’s world of comical inefficiency and freedom.

My favorite of these two films is Play time – a film about a modern and robotic Paris.

Play Time is French director Jacques Tati’s fourth major film, and generally considered to be his masterpiece. It was shot in 1964 through 1967 and released in 1967.

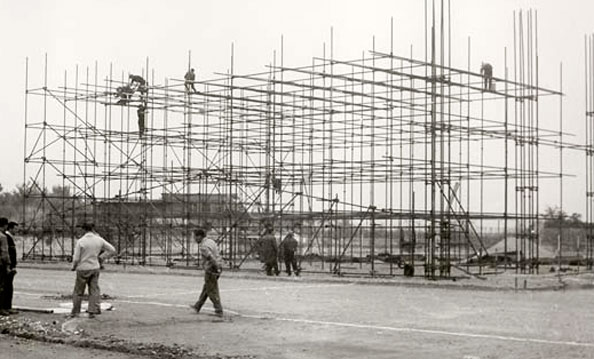

Play Time was the most daring and expensive work of Tati’s career; it took him nine years to complete and he was forced to borrow heavily from his own resources to complete the picture. For Playtime, Tati fabricated a set (dubbed ‘Tativille’) on the outskirts of Paris that emulated an entire modern city.

In the film, Tati and a group of American tourists lose themselves in a futuristic glass-and-steel Paris, where only human nature and a few hints of an older France still emerge to breathe life into the city. Narratively, Playtime had even less of a plot than his earlier films, and Tati endeavored to make his characters, including Hulot, almost incidental to his portrayal of a modernist and robotic Paris.

“If Play Time has a plot, it’s how the curve comes to reassert itself over the straight line.”[1] This progression is carried out in numerous ways. At the beginning of the film, people walk in straight lines and turn on right angles. Only working-class construction workers (representing Hulot’s ‘old Paris’, celebrated in Mon Oncle) and two music-loving teenagers move in a curvaceous and naturally human way. Some of this robotlike behavior begins to loosen in the restaurant scene near the end of the film, as the participants set aside their assigned roles and learn to enjoy themselves after a plague of opening-night disasters. Throughout the film, the American tourists are continually lined up and counted, though Barbara keeps escaping and must be frequently called back to conform with the others. By the end, she has united the curve and the line (Hulot’s gift, a square scarf, is fitted to her round head); her straight bus ride back to the airport becomes lost in a seemingly endless traffic circle that has the atmosphere of a carnival ride.

The Trailer

[youtube width=”590″ height=”400″]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sVTfUe8jM3o[/youtube]

![Postcard collection from Expo 67 [repost]](https://www.joehallock.com/wp-images/2017/07/expo67_077.jpg)

Leave A Comment